CAT 2025 is just 105 days away and all aspirants must start solving CAT level questions. So herfe is iQuanta with the daily CAT quiz that tests your ability and preparedness for the exam. Take this CAT Quiz and assess your performance that will help you identify your stregths and weaknesses. These questions have been designed by our experts to test your knowledge and the level of your CAT preparation. Start with this quiz and take up this challenge that will boost your confidence.

Join this free whatsapp group to get the latest information about CAT exam along with the strategies by CAT experts

RC 1

Critics of Goldman Sachs love to say the investment bank highlights the failures of everything from capitalism and neoliberalism to democracy and socialism. Millions of words have been written depicting Goldman as the central villain of the Great Recession, yet little has been said about their most egregious sin: their lobby art. In 2010, Goldman Sachs paid $5 million for a custom-made Julie Meheretu mural for their New York headquarters. Expectations are low for corporate lobby art, yet Meheretu’s giant painting is remarkably ugly— so ugly that it helps us sift through a decade of Goldman criticisms and get to the heart of what is wrong with the elites of our country.

Julie Mehretu’s “The Mural” is an abstract series of layered collages the size of a tennis court. Some layers are colorful swirls, others are quick black dash marks. At first glance one is struck by the chaos of the various shapes and colors. No pattern or structure reveals itself. Yet a longer look reveals a sublayer depicting architectural drawings of famous financial facades, including the New York Stock Exchange, The New Orleans Cotton Exchange, and even a market gate from the ancient Greek city of Miletus.

What are we to make of this? Meheretu herself confirms our suspicion that there is no overarching structure to the piece. “From the way the whole painting was structured from the beginning there was no part that was completely determined ever. It was always like the beginning lines and the next shapes. So, it was always this additive process,” she said in an Art 21 episode.

Does all art need a strict and coherent structure? Of course not. Yet consider Mehretu’s mural in juxtaposition with Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings. Both are large, abstract, and improvisational. Pollock painted by moving the canvas to the floor and dripping paint down, making the act of painting more akin to dance. Meheretu made her piece on a computer and then had a team of assistants actually paint it on the wall. Pollock’s jazz-inspired swirls and textures evoke raw emotion unfiltered. They invite us to look at the painting as a painting, and not for some further content. If there are any defenders of the Goldman mural, they’re probably hiding behind similar arguments and offering platitudes appealing to the idea of expression for the sake of expression: that the painting justifies itself simply by existing. However, Meheretu does not allow for this easy out. Unlike Pollock, she includes something more than paint: the facades of famous financial buildings, by which she implies artistic argument, content outside of form.

So, what is the painting trying to say? Nothing. The glimmers of old-world beauty demand to be accounted for, and yet because there is no coherent structure to the piece, we can find no true justification for their inclusion, other than that they reference who paid for the painting. Again, Mehretu’s own words confirm what is immediately visible: “I think there’s a lot of meaning in the painting, but I would never want to articulate a direct statement. I think maybe that’s a big reason I work with abstractions so that you can’t necessarily pinpoint a specific narrative.”

RC 2

The Use of Lateral Thinking is a short book with a long reach. Providing no more than a few slight examples of how lateral thinking might work in practice – largely on the perception of shape and function in geometric forms – it proposed four vague principles for problem-solving and creativity: the recognition of dominant polarizing ideas; the search for different ways of looking at things; a relaxation of the rigid control of vertical thinking; and the use of chance.

Lateral thinking was not, Edward de Bono (a Maltese physician and medical researcher who turned his back on academia to become a student of creativity) conceded, ‘a magic formula’ to be learned and used at will. ‘No textbook could be compiled to teach lateral thinking,’ declared the future author of Lateral Thinking: A Textbook of Creativity (1970), as well as The Five-Day Course in Thinking (1968), Practical Thinking (1971) and Teach Yourself to Think (1995). For now, the would-be lateral thinker would have to make do with a few suggestive leads. Try using visual images as your ‘material of thought’. Think by analogy. Adopt a random position. Unthinkingly select an object to stimulate association.

For readers who were wondering what science lateral thinking was based upon, de Bono’s book The Mechanism of Mind (1969) left the matter unresolved. Nerve networks in the brain, he declared – omitting to mention any neurological research or cognitive studies – permitted information to organize itself into sequences or patterns that were usually asymmetric, like rain channeled into streams and rivers. As efficient as this self-organizing system was at setting up patterns, the asymmetry caused thinkers to proceed only along the main channels.

Lateral thinking left academics from all disciplines nonplussed. For philosophers, formal logic didn’t equate to the actual processes in which a thinker is engaged when reasoning: it was a means of testing the validity of conclusions already reached. Historians of science questioned why de Bono invested so much in the genius ‘eureka’ moment, when invention and paradigm shifts were more commonly the work of communal endeavor and disputation. Intellectual historians wondered how Greek philosophy had stymied lateral thinking (the alphabet and literacy had, surely, played an altogether more vital role in the cognitive retooling of the modern mind), and reminded de Bono that the Ancient Greeks had many ‘irrational’ byways for pursuing insight and inspiration.

Psychologists had more questions than most. Lateral thinking clearly overplayed the importance of the creative breakthrough at the expense of trial and error, feedback and reflection, not to mention unconscious incubation.

Though de Bono’s attack on Western logic and traditional pedagogy chimed with the countercultural zeitgeist, lateral thinking was destined to find its most starry-eyed acolytes in a world that the New Age had quietly passed by: business management, where de Bono soon acquired a reputation as a consultant and lecturer. Doing the rounds of Shell, IBM and DuPont, he seized his moment, unleashing a stream of books and courses that were as notable for their unabashed upselling as their signature bombast and newly minted terms. ‘Operacy’: the skill of thinking leading to action. ‘Fractionation’: taking an existing idea and breaking it into parts to be rearranged to spark new ones. ‘Random-input method’: selecting a random word or object and applying it to the problem at hand. ‘PO’: a provocation used to move thinking forward. The neologisms kept on coming, lending a shiny gloss to every new iteration of lateral thinking.

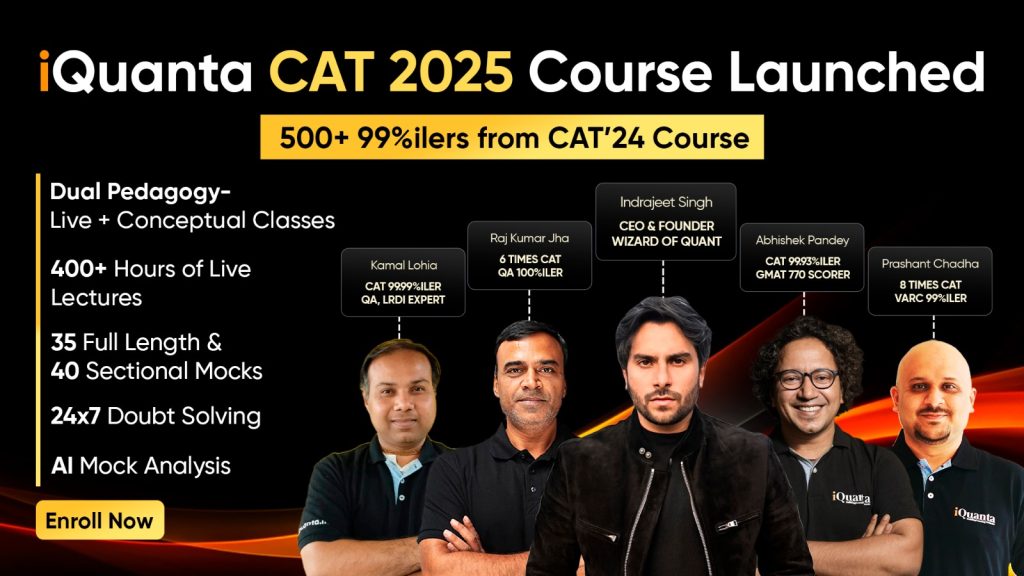

iQuanta CAT Course 2025