CAT 2025 is just 109 days away and it is the right time to start solving CAT level questions. Take this CAT Quiz and assess your performance and preparedness for CAT exam. These questions have been designed by our experts to test your knowledge and the level of your CAT preparation. Start with this quiz and take up this challenge that will boost your confidence.

Join this free whatsapp group to get the latest information about CAT exam along with the strategies by CAT experts

RC 1

A timeless universe is hard to imagine, but not because time is a technically complex or philosophically elusive concept. There is a more structural reason: imagining timelessness requires time to pass. Even when you try to imagine its absence, you sense it moving as your thoughts shift, your heart pumps blood to your brain, and images, sounds and smells move around you. The thing that is time never seems to stop. You may even feel woven into its ever-moving fabric as you experience the Universe coming together and apart. But is that how time really works?

According to Albert Einstein, our experience of the past, present and future is nothing more than ‘a stubbornly persistent illusion’. According to Isaac Newton, time is nothing more than backdrop, outside of life. And according to the laws of thermodynamics, time is nothing more than entropy and heat. In the history of modern physics, there has never been a widely accepted theory in which a moving, directional sense of time is fundamental. Many of our most basic descriptions of nature – from the laws of movement to the properties of molecules and matter – seem to exist in a universe where time doesn’t really pass. However, recent research across a variety of fields suggests that the movement of time might be more important than most physicists had once assumed.

A new form of physics called assembly theory suggests that a moving, directional sense of time is real and fundamental. It suggests that the complex objects in our Universe that have been made by life, including microbes, computers and cities, do not exist outside of time: they are impossible without the movement of time. From this perspective, the passing of time is not only intrinsic to the evolution of life or our experience of the Universe. It is also the ever-moving material fabric of the Universe itself. Time is an object. It has a physical size, like space. And it can be measured at a molecular level in laboratories.

The unification of time and space radically changed the trajectory of physics in the 20th century. It opened new possibilities for how we think about reality. What could the unification of time and matter do in our century? What happens when time is an object?

RC 2

Classicism is a broad river that has run through Western architecture for two-and-a-half millennia. A generation ago it seemed that the stream had reduced to a trickle. Only a small phalanx of recondite architects really understood the classical language of architecture; they were generally employed by private patrons whose social as well as architectural ideas were not at the cutting edge. And yet now, if not quite in full slate, the river has recaptured a degree of vigor. The flow has quickened, the banks are beginning to brim. What has happened, and what does the future hold?

Since this represents a revival, a word should be said on this subject at the outset. Revivals are a constant— indeed inevitable—theme of classical architecture, to the point of being almost a defining feature. Even Greek architecture, later regarded as the fons et origo of the classical system, evolved out of—and harked back to— an ancient tradition, now lost. It may have been deliberately archaic, using past forms beyond their natural sell-by date. To engineers, post-and-lintel construction, which forms the basis of all Greek architecture, is inferior to the arch, which can be built cheaper, using smaller pieces of stone. And yet the Greeks cannot have used it in ignorance of the arch; arches were being used elsewhere in the ancient world and travelers must have seen them. Trabeation had a meaning for the Greeks, perhaps rooted in earlier phases of their culture.

The classical orders—Doric, Ionic, Corinthian —are similarly mysterious. We cannot be sure what they conveyed to the Greek mind. During the Enlightenment, the Jesuit theorist Laugier believed that classical architecture had developed from nature itself and mankind’s primitive needs. A Doric temple such as the Parthenon expressed the same building principles as a hut made from tree trunks; a more sophisticated society had substituted marble for wood, but vestigial traces of the timber origins could still be seen. But one only has to look at the broadly contemporary Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae, on its Arcadian hilltop, to realize that such rationalist explanations do not suffice. At Bassae, the interior Ionic order is attached to spurs or fins set at an angle to the walls of the cella, the focus of which is the earliest known use of the Corinthian order. This does not, however, appear on a screen of columns, but rather on a single column, in a central position in front of the sanctuary. Was it somehow related to a representation of the deity within? The meaning is lost. We can imagine, though, that the form developed from an earlier tradition, whose symbolism would have been obvious to the community. An early instance of reinterpretation—or revival? The Parthenon itself can be construed as revivalist, since it was built as an act of national reaffirmation after the buildings on the Acropolis were destroyed by the Persians in 480 B.C. After the destruction, the sacred stones of the old structures were gathered up and buried before the new temples were built. The new buildings were rooted in the past. Classicism always looks back as it moves forward.

Every subsequent phase of classicism after the Greek period was to some extent a revival, invoking the associations of a golden age. The Romans borrowed the architectural clothes of Greece. In the eighth century, Charlemagne, declaring himself Holy Roman Emperor, sought to revive the glory of Rome. The Carolingian gatehouse at the Abbey of Lorsch, in Germany, may not look immediately like the Arch of Septimius Severus in Rome because it is faced in red and white tiles and is surmounted by a pitched roof with a bell turret. But materials—or even appearances—are not the point. Its creator was restating an idea as best he could— reaffirming a continuity.

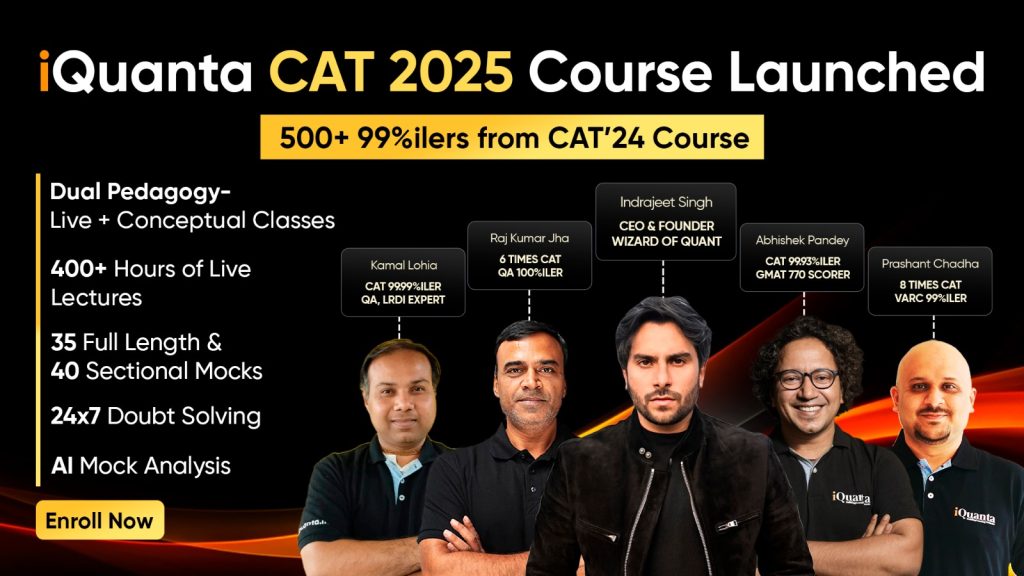

iQuanta CAT Course 2025