CAT 2025 is just 107 days away and all aspirants must start solving CAT level questions. So herfe is iQuanta with the dailuy quCATi quz that tests your ability and preparedness for the exam. Take this CAT Quiz and assess your performance that will help you identify your stregths and weaknesses. These questions have been designed by our experts to test your knowledge and the level of your CAT preparation. Start with this quiz and take up this challenge that will boost your confidence.

Join this free whatsapp group to get the latest information about CAT exam along with the strategies by CAT experts

RC 1

Prime ministers announce changes to government structures for one of two reasons. Either they are frustrated in pursuit of some cherished policy, or they are panicking that events are running away from them. Moving Whitehall furniture creates a comforting illusion of control.

Since Boris Johnson doesn’t cherish much beyond the idea of himself as a figure of greatness, the safe bet is that his plan to merge the Foreign Office with the Department for International Development belongs in the category of gestural distraction. The rationale is that a hybrid ministry will more efficiently represent the interests of “global Britain”. It calls to mind the late Denis Healey’s maxim that the moment to remove a man’s appendix is not when he is busy carrying a piano up a flight of stairs.

Instead of performing non-essential surgery on an exhausted government machine, the prime minister might more usefully bolster the UK’s international reputation by competently handling a public health emergency and incipient economic crisis. But Johnson did not go into politics for the love of managerial capability, nor was that the basis on which he appointed his cabinet. The prime minister’s departmental merger announcement in the Commons on Monday was drowned out by the screech of tyres on Downing Street, executing an emergency U-turn over free school meal vouchers. The choreography hardly advertised steady statecraft.

The coronavirus outbreak would have tested a strong ministerial team. It cruelly exposes those whose all-consuming ambition for a top job has driven out any grasp of what doing the job well might involve. Gavin Williamson is the exemplar. I single out the education secretary not because he is unusually weak but because he is typically weak. The bungling inability to steer schools safely out of lockdown is his personal failure, but also symptomatic of an attitude to government that puts someone so likely to fail in charge of something so important.

If children are not allowed to throng in classrooms, there is going to be a shortage of teachers and space. That was a foreseeable problem of logistics, not an ideological battle, which might explain why the government has failed to think it through. The Johnson administration evolved from the campaign to sweep Brexit unbelievers aside, and it hasn’t shaken the habit of treating every problem as a hunt for enemies. That was the muscle memory in action when Williamson kicked education unions for “scaremongering” about the threat of Covid-19 in the classroom. It turned out parents were just as wary of the disease as teachers.

Williamson is not unskilled in politics, just unsuited to the bit that involves governing. He is credited as the fixer behind Theresa May’s confidence-and-supply deal with Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionists – not the noblest legacy but a nifty feat of political cut-and-shut to get a wrecked prime minster back on the road after electoral humiliation. Then Williamson got greedy. He fancied himself as a statesman and future leader, to which end he needed a big department on his CV. He was given the Ministry of Defence, where his inadequacies were exposed.

RC 2

On the first day of the semester, I try to give my students an impression of what the philosophy of science is about. I begin by explaining to them that philosophy addresses issues that can’t be settled by facts alone, and that the philosophy of science is the application of this approach to the domain of science. After this, I explain some concepts that will be central to the course: induction, evidence, and method in scientific enquiry. I tell them that science proceeds by induction, the practices of drawing on past observations to make general claims about what has not yet been observed, but that philosophers see induction as inadequately justified, and therefore problematic for science. I then touch on the difficulty of deciding which evidence fits which hypothesis uniquely, and why getting this right is vital for any scientific research. I let them know that ‘the scientific method’ is not singular and straightforward, and that there are basic disputes about what scientific methodology should look like. Lastly, I stress that although these issues are ‘philosophical’, they nevertheless have real consequences for how science is done.

At this point, I’m often asked questions such as: ‘What are your qualifications?’ ‘Which school did you attend?’ and ‘Are you a scientist?’

Perhaps they ask these questions because, as a female philosopher of Jamaican extraction, I embody an unfamiliar cluster of identities, and they are curious about me. I’m sure that’s partly right, but I think that there’s more to it, because I’ve observed a similar pattern in a philosophy of science course taught by a more stereotypical professor. As a graduate student at Cornell University in New York, I served as a teaching assistant for a course on human nature and evolution. The professor who taught it made a very different physical impression than I do. He was white, male, bearded and in his 60s – the very image of academic authority. But students were skeptical of his views about science, because, as some said, disapprovingly: ‘He isn’t a scientist.’

I think that these responses have to do with concerns about the value of philosophy compared with that of science. It is no wonder that some of my students are doubtful that philosophers have anything useful to say about science. They are aware that prominent scientists have stated publicly that philosophy is irrelevant to science, if not utterly worthless and anachronistic. They know that STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) education is accorded vastly greater importance than anything that the humanities have to offer.

Many of the young people who attend my classes think that philosophy is a fuzzy discipline that’s concerned only with matters of opinion, whereas science is in the business of discovering facts, delivering proofs, and disseminating objective truths. Furthermore, many of them believe that scientists can answer philosophical questions, but philosophers have no business weighing in on scientific ones.

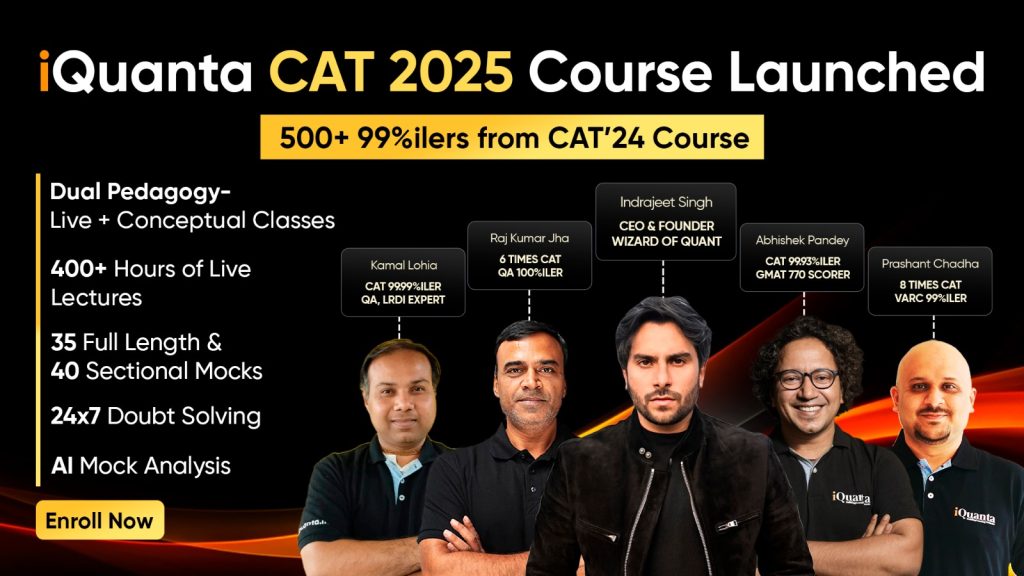

iQuanta CAT Course 2025